After a sincerely ambitious beginning, this blog seems to have hit a fallow stretch. This isn't that surprising -- most of what I do, I do in fits and starts. But it was a little disappointing. I was busy and all that, of course, but I always am, and was when I started this blog, so I'm not going to pin the blame on that. It could have been entirely possible for me, I think, to discipline myself to write in stolen moments, like Lindsay put it. One pretty significant obstacle is just that I haven't quite gotten used to the idea of writing bloggishly -- which is somewhere between a conversation and a short paper, I suppose. I think I've been erring on the side of writing essayistically, holding myself up to (disavowed?) academic standards without having an academically allocated schedule that would let me properly satisfy them.

It's funny, because there definitely are media, or genres, where I feel completely at ease in shooting from the hip -- it's what I really enjoy about giving interviews, for example, or conducting lectures and seminars, which I've always almost entirely improvised. I want to try to bring that here, and write with a bit more dedication and a bit less worry, I suppose.

I figure that a good way to get things moving again would just be to go through the dozens of half-finished and half-started drafts that I have, sitting in ~/src/feral_machines/content/posts/scratch, and give any that aren't completely hopeless a sentence or a paragraph (or several) in the sun, and move on. So, here it goes.

Table of Contents

- Lack and Leak

- Weird Machines and Eerie Algorithms

- The Lure of Triviality

- Writing with GPT-2

- The Punctum Next Door

- Gender Fatigue

- The Real Ethics of Computer Science

- Metalanguage and Metacomedy

- Types of Obscurity

- drone.c

- Hello, Inspector

- Modularity in Philosophy

- 'Recursivity'

- Self-Identification

- The Eight Root Statements of the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus as Completed by GPT-2

- Epilogue

Fragments

Lack and Leak

Over on the &&& blog, Valentin Golev takes a couple of stabs at modeling the Lacanian concept of lack -- specifically, that of a "lack in the Other", which is structurally critical to the formation of subjectivity, in the context of Lacanian psychoanalysis -- in the domain of computation. I didn't find it very compelling, on the whole, but there was one interesting moment in there, where lack is essentially understood in terms that amount to a leak in the abstraction layer called 'the Other'. It's tempting to climb back up the wick of Golev's analogy, and see how far we can get, recasting psychoanalytic theory in computational, and specifically information-security oriented terms. Trauma as a 'weird state'? Symptoms as side-channels? Pathologies as weird machines? A long time ago, I remember seeing someone on twitter (I think her handle was 'ʞ'?) tweet

s/attack surface/erogenous zone/

which would be a fascinating place for this to wind up.

While mulling this over, I stumbled across a chapter in John Johnston's The Allure of Machinic Life which detailed the use that Lacan himself had made of automata theory, at times (circa Seminar II) modeling the "symbolic order" in terms of finite state machines -- the same formalisms that Halvar Flake uses uses to codify the general theory of weird machines and exploitation, so there might be better means than I expected for establishing some sort of correspondence between the two domains.

Weird Machines and Eerie Algorithms

The are probably less than ten people in the world who have asked themselves, "ok, what relation does the 'weird' in 'weird machines' have with the 'weird' Mark talks about in The Weird and the Eerie", but I bet each of those ten people ask themselves this on a pretty regular basis. So I had the idea of writing a post on the topic, maybe with the additional conceit of comparing and contrasting two modes of fascination with the strangeness of computation: I want to write something about how weird machines operate libidinally, or aesthetically, in the "hacker spirit" -- how they fascinate and become objects of desire. And I'd also like to write something about the way in which machine learning algorithms have gripped the public imagination -- especially the imagination of those for whom the algorithms themselves are an inscrutable black box, those who speak of "algorithms" in hushed tones, but who couldn't implement a FizzBuzz to save their mother's life. But maybe also the imaginations of those who work day and night in machine learning. I've been kicking around the idea that it might be interesting to try to cast these technological affects, or genres of technological discourse, in terms of K-Punk's conceptual distinction between the weird and the eerie. See if that holds any water.

The Lure of Triviality

Every now and then, I'm reminded of something I must have read (or heard?) somewhere, concerning the use of tautologies, or near tautologies, in political rhetoric. For years, I've had some vague sense that I'd read something extremely illuminating on the subject... somewhere. I've never been able to remember the source, itself, though. And, come to think of it, my memory of what that source had actually said has faded over the years as well, so I might as well take a stab at a clean room reconstruction of the topic.

What I have in mind, here, specifically are "trivially true" statements transformed into political slogans. By "trivially true", I mean to include both statements that, at least on their surface, are clothed in the syntactic form of a tautology, as well as statements that make a show of cleaving so closely to common knowledge as to convey no new information at all -- slogans that, for all intents and purposes, seem semantically vacuous.

The question I want to ask, then, is just: What's the point? What political function is achieved by trafficking in "semantically vacuous" slogans?

Now, my reasons for seeing things this way might be an effect of my rather partisan salience filters, but it seems to me that the discursive strategy I'm talking about is principally wielded by the Right, and by its reactionary, populist tail, in particular

A few examples that come to mind are:

- Men aren't women -- a slogan glibly employed by TERFs and other anti-trans agitators.

- Boys will be boys -- when used to dismiss concerns about sexual violence.

- All lives matter -- the popular retort by which white supremacists (be they tacit or explicit) most frequently dismiss the eponymous battle cry of the Black Lives Matter movement.

- It's okay to be white -- the slogan of choice in a recent white supremacist postering campaign.

- La France aux Français -- a perennial rallying cry of French nationalists and xenophobes, whose triviality hinges on concealing the difference between "those who live in France" and "the French", but whose virulence depends on exploding it.

These aren't scissor statements, in Scott Alexander's sense -- statements that sow discord by striking one group as profoundly, viscerally wrong and another (which will thereby be christened its outgroup) as unquestionably correct. These statements are deliberately void of any genuine locus of disagreement, at least when taken literally. They are intended, after all, to seem "trivially true".

As polemical slogans, however, their explicit intent is divisive. How can a statement whose literal content is, if not outright empty, utterly uncontroversial, be used in this way?

Both the proponents and adversaries of these slogans know full well that their real content has been studiously drained from the words themselves, only to be held, knowingly, in a contextual reserve. Neither immediate party to the conflict mistakes the semantically hollow flasks that become the slogan's literal form for its hidden partisan content.

Crucially, though, there is an audience who will, by design, read these slogans as "trivially true", and who are, in virtue of that fact, their target market: those outside the immediate conflict, the bystanders and "normies" -- who I suppose we could call the "side-group" of the attack, to distinguish them from its ingroup and outgroup.

What does this audience see? They see one group trying to defend basic, undeniable truths and common sense, excruciatingly modest in actual content, and another objecting hysterically, grinding "logic" and "basic common sense" into dust, telling the audience that they too are culpable should they believe such pernicious messages as "men aren't women", that "all lives matter", or that it's even so much as "okay" to be white.

I. Rohl develops this line of argument convincingly in her Medium post, Put in Some Fucking Effort, putting their finger on the manner in which situating these slogans in a debate, itself, is sufficient to infuse them with some of their otherwise absent content:

In particular, uttering a sentence in response to what someone else has said will suggest that one thinks the content of one’s utterance relevant to what came before, and so will insinuate whatever auxiliary assumptions would be needed to make it relevant. If the structure of the conversation sets up an utterance as a refutation or counter-point, the utterance will convey that one thinks that it is at odds with with the commitments of one’s interlocutors. These considerations allow bad actors to make an utterance that clearly communicates hateful or objectionable content, and then use literal paraphrase and decontextualization to present themselves as wronged parties condemned for defending innocuous or demonstrably true positions.

The article goes on to present an excellent dissection of how this strategy is used in TERF discourse, with an illuminating detour analysing its analogue in the use of the "All Lives Matter" slogan.

Does an analogous strategem have a place on the Left, or is this a strictly Rightist form of sophistry? (And, if the latter, is this for essential or accidental reasons?)

An analog that does leap to mind is:

which sort of logically resembles "men aren't women" (which looks like its reactionary counterpart), and which has the syntactic form of a tautology, as much as "red apples are apples" does. But I think that the analogy is ultimately superficial. Those who assert this statement generally do not expect immediate, trivial assent outside of a certain ingroup.

When Leftists elect to cast their slogans in the style of a tautology, or an argument from definition, it's typically the definition itself that's loaded with polemical charge. The move being made here is less an appeal to an established definition (be it of "woman", of "racism", or whatever), than a succinct call to recast the definition at stake.

This is markedly different from the right-populist, or reactionary, tactic, which holds slogan's charge in connotative reserve. The reactionary's audience is not expected to debate whether, in fact, men are actually women (though they may well dispute the implicit premise that trans women are actually men!), or whether all human lives matter, or whether it's okay to be white, or whether boys will be what they are.

It's unsurprising that the populist kneejerk against this slogan has, itself, a way of adopting a tautological form, as it does in the mouth of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, around the 3-minute mark of this interview:

so, when people talk about, you know, 'are transwomen women?', my feeling is: transwomen are transwomen

The tactic I'm speaking about, here, then, appears to bear an essential connection to reactionary -- specifically, right-populist -- discourse. Its charm lies in its appeal to "the way things just are", to the simple "facts of the matter", to "common sense" or "simple logic" -- to the obvious, to what requires neither criticism nor scrutiny.

It's interesting to observe how the formal signature of these slogans, alone, is often enough to signal a political kinship across traditionally dividing lines. In a post on the conservative New Zealand blog, Whale Oil, entitled What Renee Gerlich and Lauren Southern Have in Common, we see this played out in some detail.

It's possible that the capture of right-populist sympathies, I think, is one of the deliberate aims of this style of rhetoric. The recent uptick in its use, after all, coincides with the appearance of campaigns like Hands Across the Aisle, whereby "gender critical feminists" make a show of explicitly declaring themselves the allies of the American Right.

I think I'd need to dig a bit deeper, though, before I'm sure of the roots of this trope's appeal to the reactionary mind.

Writing with GPT-2

Pale River was composed in a weird (eerie?) sort of dialogue with the GPT-2 117M language model. I'd write a few lines of text, pass them to the model as a prompt, then take its response and select whichever phrases I felt resonated, rework them a little, combine them with a few words of my own -- sometimes the initial material, sometimes something new -- and then reply to the model with the result, repeating the process over and over again, as the poem took shape.

The process became completely absorbing, this latching onto a stream of consciousness with a prosthetic unconscious (I suppose there's some sense in which this is always what we're doing, but not in this sense, in particular.) I've always loved having some element of heteronomy in the writing process -- using cut-up, or Markov chains, or some other semi-aleatory constraint -- but this felt different: GPT-2 feels both more autonomous and less... separate than those older instruments. It picks up subtexts, rhythms, and themes from the texts you pass it, and the dream sequences it draws from them are alien and intimate in equal measure.

I wonder how it will look when the fog of novelty starts to disperse, and if texts generated by or with GPT-2 will start to betray predictable artefactual signatures, the way DeepDream's dog-addled images eventually did.

Fine Tuning the Model on Slack Logs

When I later experimented with fine-tuning the model by training it on a fairly large (6,520,923 words) corpus of Slack logs, quite possibly to the point of overfitting things somewhat, I did start to notice the bones of recursion poking through the surface of the text. These patterns were fascinating in that they appeared responsible for both the most eerily self-aware and most stupidly mechanical moments of the text: self-reflection and quotation, on the one hand, and blind repetition, on the other. (There's an echo of Slovenian Idealism, here...)

You can see both aspects plainly in the following sample, for example (to be perfectly clear, this transcript is entirely artificial; none of the characters here has ever said anything semantically equivalent, or even similar, to what you're about to read -- stylistically, maybe):

SAMPLE 1

2017-11-21 02:06:06 mark "not just with me" isn't even the first quote to be used with @danny)

2017-11-21 18:04:44 peligrietzer yeah, it was really just 'we're not going to be able to get him out'

2017-11-21 18:15:52 peligrietzer a very nice point

2017-11-21 18:23:08 peligrietzer the point is in a very specific sense

2017-11-21 18:23:20 peligrietzer i think i'd say that he would be a good thing to be back in the club

2017-11-21 18:34:22 peligrietzer but he's one of those guys you know that was really nice to see a little bit when someone left the club (i've never met some of those guys) and got into a bunch of controversies with the club

2017-11-21 18:37:00 peligrietzer anyway, I feel like this seems like a pretty good one

2017-11-21 18:39:08 peligrietzer yeah, i think that the real value of club is that the club itself is pretty nice

2017-11-21 18:39:16 * peligrietzer says 'we are not going to leave the club, we just need to get back here, get on the team ASAP, and have a good game'

2017-11-21 18:40:19 peligrietzer if the club can help get the club back, that's going to be a great move

2017-11-21 18:40:19 if we don't manage to get back here (again, i don't think it's an easy matter to get the club back, as i've never had a club to support) it won't look like they'll do it again so i don't have any better way to get them back.

2017-11-21 18:40:30 peligrietzer i have a hunch that their next contract, if you want to put me in charge, probably has a lot of issues to work with

2017-11-21 18:40:33 peligrietzer also, if there's a thing i can't think of, here's one in which one of the founders has a long history of violence against women as a side-benefit

2017-11-21 18:43:02 peligrietzer so, again, he's the dude @kittenberg is supposed to be with now :b.in

2017-11-21 18:47:28 peligrietzer i could probably just have him and me having a discussion about what the fuck the rest of the club is really like

2017-11-21 18:56:08 dheeraj.chand I've been trying to read the club's membership file for a while, and the club is pretty fucking bad

2017-11-21 18:56:11 dheeraj.chand So I have a bunch of stuff i need to figure out, and i'll probably have to use a bunch of other stuff too.

2017-11-21 18:56:23 dheeraj.chand My second order of business would be to get some feedback from some of your guys, and i have a really, really strong feeling they want it and will want to help, but the club is in a weird position on its own

2017-11-21 18:56:26 peligrietzer yeah, i just got this quote

2017-11-21 18:56:39 dheeraj.chand "we're not going to leave the club, we just need to get back here, get on the team ASAP" (actually, that might be the most powerful of words, because it's actually kind of obvious they want to leave the club, but i think the context is somewhat ambiguous. it's basically a statement that the club's not going to stay, it's already been sold)

2017-11-21 20:23:09 dheeraj.chand "We're basically in the middle of a bunch of big shit to try to get through, but it might help you if that's your first move"

2017-11-21 20:25:22 dominic.fox @danny i really need to read this...

2017-11-21 20:25:22 "we're basically in the middle of a bunch of big shit to try to get through"

The model has clearly clued into several salient patterns, here -- from simple patterns concerning the format of WeeChat logs, including sanely incrementing timestamps, all the way to the much more "human" patterns of topic continuity (which it cleverly correlates with the timestamps, if you look closely -- changes in subject correspond to temporal gaps of more than an hour), and, most strikingly, quotation, reflection, and belief attribution, as seen in Pseudo-Dheeraj's remark at 18:56:39 (in bold). The effect is truly eerie: a skeletal self-awareness in whose light self-awareness itself seems something startlingly skeletal.

The Punctum Next Door

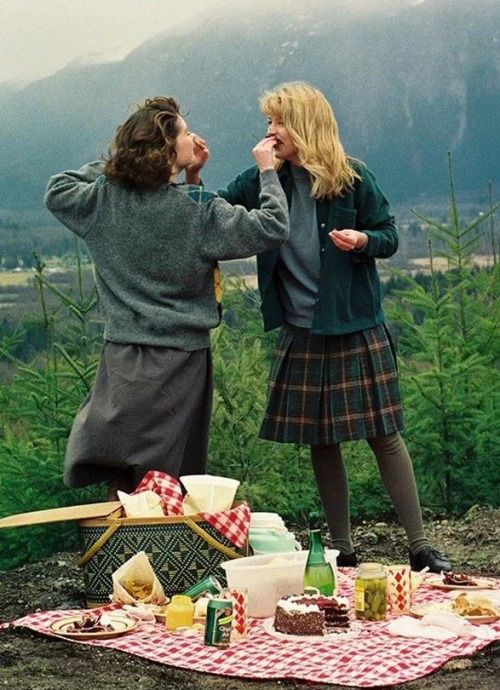

There's a convention, which seems particularly popular in American TV, of presenting feminine beauty by means of a pair of characters. One character's job is to represent socially legible beauty, a beauty that every member of the audience knows no member of the audience would dispute. The other's role is to be the one that you, the viewer fall for -- the one whose beauty each member of the audience (or a certain swath of the audience) recognizes while believing, on some level, that they alone recognize it.

This trope neighbours, but isn't quite, the archetypal dichotomy of "the Virgin and the Whore", if only because it appears to be presented without any evident hostility for the first woman. What matters for it is that the viewer believe that the rest of the world is utterly taken with the first woman, while he alone sees past all that surface glamour, and somehow, on some phantasmatic plane, has struck a real connection with the second woman.

Veronica and Betty, who I think first appeared around 1950, might be the oldest instance of this dichotomy that still has some sort of cultural currency. Ginger and Mary-Ann, from Gilligan's Island, might be the pair who really saw this trope come into its own. Firefly picked up the torch with Inara and Kaylee. Laura and Donna, in Twin Peaks, arguably instantiate this trope as well -- but the "deepening" effect seems to be directed back into the diegetic frame, as an element of James' character (aside: how much of the peculiar eerieness, of Lynch's work, or at least its sense of haunting irreality, comes from subtly embedding viewer-oriented conventions back into the diegetic frame?). I think the role of capturing the viewer's attention might fall more to Audrey, in any case.

The various instantiations of this trope are strangely consistent in several details -- what role is played by the apparently necessary difference in hair colour between the two, for example? Why is one woman's hair always dark, and the other's always light? Which one has which colour seems to be unimportant -- sometimes it's the first woman who has the light hair, sometimes it's the second -- but there's always a contrast, as if to signal nothing other than that there's some sort of dichotomy at play here. (The only examples that I can think of, off the top of my head, involve white or light-skinned Latina women -- but maybe I'm depending too much on the hair colour cue in recognizing this trope.)

There's a shade of Roland Barthes' distinction, here, between studium and punctum, I think (though I haven't read Camera Lucida in ages, so the memory's hazy). The language this culture uses to describe love almost always involves some contrast between superficiality and depth, universal legibility and singularity, so I suppose it's not surprising that tropes like this exist. Maybe this goes back to Romanticism.

Gender Fatigue

A consequence of the rate at which trans people get tired (utterly weary and bored shitless) of talking about transness, and all its associated categories, is that the vast majority of The Discourse, these days, is conducted by the newly hatched. It feels like a chore, after a while. At best, a civic duty.

The Real Ethics of Computer Science

Lucca: an analogy just occurred to me between virtue ethics, and the approach that SICP argues we should take to programming, where, rather than trying to solve the problem at hand, you first design a language in which problems like the one you're interested in can be succinctly formulated and easily solved. (Grothendieck's parable of the hammer and the sea water has the same form.)

Lucca: virtue as a domain specific language for ethical problems

Lucca: instead of tackling ethical quandries head on, you cultivate the virtues that will allow them to be grasped with as much clarity and nuance and possible, and which will make acting ethically with respect to them relatively easy

Lucca: most of the lasting contributions to the art of programming, too, tend to take the form of identifying virtues and vices.

Dominic: "Code smells" are vices rather than bugs as such.

Lucca: exactly

Lucca: and the sages of the discipline -- the Knuths, the Sussmans and Abelsons, the Sergeys -- are very good at preaching virtues

Lucca: I mean, Langsec is mostly virtue theoretic

Dominic: Somewhere in this there's a good blogpost/paper about "the real ethics of computer science"

Metacomedy and Metalanguage

Two observations:

- The original version of The Office was, and remains, one of the greatest comedies ever made.

- Its creator, Ricky Gervais, was, as remains, an atrociously poor comedian.

These observations aren't unrelated. The genius of The Office was in its agonizingly sustained meta-comedy. Gervais played his insufferable brand of humour to the hilt in the character, David Brent, pushing its failure as comedy to its limit, while at the same time framing that comedic failure in a completely different comic metalanguage -- one that differed in every respect from the crass, unrelenting, in-your-face, self-aggrandizing stylings by which Gervais is recognizable -- carrying out a sublimation of incredible artistic power.

"The only thing I ever, ever want from art," Peli Grietzer posted a while ago,

is the ability to feel about what I could previously only feel in. Maybe my definition of bad art is 'when the object-language and the meta-language are the same'.

I think that Peli's playing on one of the most interesting motifs in Jean-Yves Girard's writings, here -- one that comes up again and again wherever he crosses paths with Tarski's semantics. He likes to make fun of formulations like

(A & B) is true if and only if A is true AND B is true

highlighting their conceptual vacuity, wherein object-level concepts are explained only with reference to their meta-level shadows, by using the same formula for logical connectives whose intuitive meaning isn't already taken for granted:

(A broccoli B) is true if and only if A is true BROCCOLI B is true

By analogy, there's a trivial way of stepping outside a situation, by doubling it, and imagining an external perspective on it all, narrativising it for us. But if that external perspective -- that "metalanguage" -- is the same, in all structural respects, as the perspective ensconced in the situation that it's trying to describe, then though it might illuminate some aspects of the situation from another angle, it doesn't really illuminate the perspective that organizes the situation in any meaningful way.

Now, you can think of the tissue of significance that knits a situation together as a structure of the same sort as the logical connectives, above, but maybe more complex, less crisp, etc. You can "represent" this situation, to yourself, say, as if you were looking in on it from the outside, but there's not much art in that, if you can't look at the structure of the presentation itself from another angle, and see it -- not something else entirely, but it -- differently.

Gervais' standup work is insufferable because it insists on submersing you back into that crass, unrelenting, in-your-face, self-aggrandizing tedium that The Office exquisitely sublimates. And it's artless because, instead of casting that object-level performance in a metalanguage that both elevates and subverts it, it simply redoubles it in a mode of presentation that is every bit as arrogant and clueless as its object.

Types of Obscurity

There are, at least, five sources of obscurity that can affect philosophical writing:

-

technical jargon (benign, non-vacuous, semantically reducible)

-

poetic cognition (benign, non-vacuous, semantically irreducible)

-

accidental ineloquence (neutral, non-vacuous, semantically reducible)

-

shibboleths (pernicious, vacuous, semantically irreducible)

-

bullshit (pernicious, non-vacuous, semantically irreducible)

There's also the obscurity of incomplete and elliptical notes. I'll come back to this.

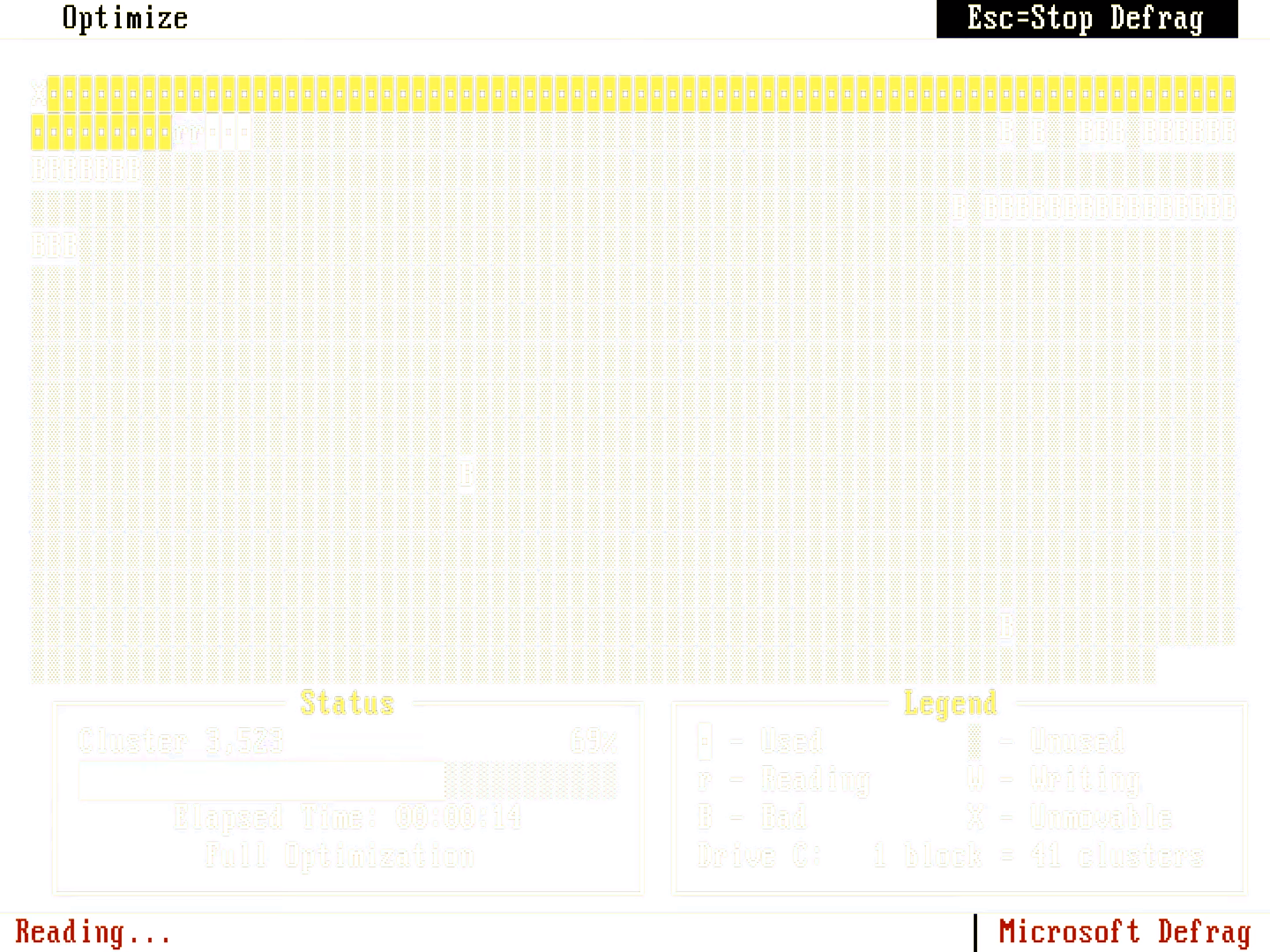

drone.c

I've been having fun, lately, playing around composing bytebeat tunes -- music expressed by very short programs, in the form of raw bytestreams, piped into aplay, or a similar program.

I was pretty happy with the way this one turned out:

#include <stdio.h>

/* sample rate: 8000 Hz. Unsigned 8 bit.

* compile with `gcc foo2.c -o foo`

* play with `./foo2 | aplay -r 8000`

*/

void main() {

long int t;

int rev = 0;

for (t=0;;t++) {

putchar(

0xFA

& (

t

& t >> 6

& ((t % (1 << 14)) < (1 << 13)?

t ^ t >> 8

: t >> 8)

/ (t <= 0? 1 : (1 + t % 32))

^ (t % 30)

+ ((t * (t>>18)) & 0xe0)

& (t > (1<<18)? t+=2 : t)

& (t < 1? rev = 0 : t)

| ((t / 10) & (t >> 14) & (t>>15) & 0xaa)

)

);

}

}

To play it compile it, run it, and pipe the output into aplay:

$ gcc ./drone.c -o drone && ./drone | aplay

where 'drone.c' is the name of the file containing the code, above. It has an interestingly ominous sound to it, I think. A kind of mounting uneasiness.

Since only the least-significant 8 bits of the 32-bit integer t are emitted by putchar(), in each iteration of the loop, using right bitshifts (>>) to key certain operations to the higher bits provides a simple way to introduce temporal development into the tune. Bitwise & operations can be used to retrict the effects of other operations to certain bits and not others, treating each bit as a distinct track, in a way.

The script below can be used to compile and encode this tune into a flac file, if you have ffmpeg and sox installed:

#! /usr/bin/env bash

prog=$1

if [ -z "$prog" ]; then

echo "Usage: $0 <source>"

exit 1

fi

p=`basename $prog`

bin="${p%.*}"

raw=${bin}.raw

wav=${bin}.wav

flac=${bin}.flac

gcc $prog -o $bin || exit 1

./$bin | tee >(cat > /dev/null) >(xxd -g1 1>&2 ) | head -c 4M > ${raw}

sox -r 8000 --no-dither --plot gnuplot -b8 -c1 -G -t u8 ${raw} ${wav}

ffmpeg -i ${wav} -acodec flac ${flac}

echo "[+] Executable compiled as ${bin}"

echo "[+] Sound saved as ${wav}"

echo "[+] FLAC encoding saved as ${flac}"

play $flac

The resulting flac file can be found HERE.

A friend of mine described this technique as minimal Komologorov complexity music, music whose apparent sonic richness is nevertheless algorithmically compressible. Interestingly, it tends to fare poorly under standard lossy compression codecs commonly used for music. Converting the bytestream to an mp3 file, for example, will drastically change the sound. If nothing else, this offers an interesting perspective on which aspects of sound, for the mp3 standard, are held canonical and which are dismissed negligible.

Hello, Inspector

is a near-homophone for "a lone spectre". Still don't know what to do with that.

Modularity in Philosophy

Over a series of emails, my friend Pat McHugh made a few suggestions about modularity in philosophy, which I've found myself thinking about every now and then:

I have an idea that a great philosophy should be somewhat modular; that there are ideas which can be applicable and amplified within other systems. That's what really keeps these ideas from ossifying. [...] I was once toying with the idea of something I called metaphysical modularity, but I don't quite remember what the idea was. I think it was something like a group of hypotheses regarding some basic ontological features which could provide a regulative nature to a number of possible metaphysical or existential commitments without having to demand that these larger commitments be the only natural or necessary resultants from these hypotheses - they would just help provide a means of testing these larger commitments in issues of consistency, verification, justification, or the incorporability of unanticipated data. What any of these basic things would be, I do not know, apart from perhaps being some kind of grammar of relationality.

It's an idea that will seem intuitively sensible to anyone working in software engineering, I think. A system that stands or falls as a monolithic whole will, under most circumstances, fall. There's a brittleness in holistic unity -- subjecting any part of such a system to revision will frequently entail major or minor revisions in every other component.

What we're talking about here, ultimately, are relations of conceptual dependency in a system of thought. Let's say that A is conceptually dependent on B if it's impossible to make sense of A without having already understood B. (We could also be looking at relations of logical entailment, but I think this conceptual intelligibility may be more fundamental, and a more pressing problem when trying to grasp the structure of philosophical systems.) Let's call a "conceptual graph" a directed graph whose nodes are concepts and whose edges represent this dependence relation.

We can then categorize philosophical systems in terms of the topology of their underlying conceptual graphs. Some systems are (or aspire to be) treelike or "arboreal" in structure, setting out first principles and deriving increasingly refined concepts from them while making an effort to avoid circularity. Others make a virtue of circularity, holding as axiomatic that the conceptual content of the first principles depends equally on those derived from it. Some systems are fragmentary by nature, consisting of several unconnected islands, each a densely interconnected clique, but with little or no connection to the rest of the conceptual archipelago.

Let's say that a system's degree of connectivity is something like

mean(out_degree(node[i]) / N, for 0 <= i < N)

where N is the number of concepts (nodes) in its conceptual graph. A "monolithic" or "holistic" system, at the limit, is a system each of whose nodes is depended upon by every other node in its conceptual graph. Another way of putting this is that the out-degree of each node is maximal, or that the graph is "fully connected" or "complete". Its "degree of connectivity" is 1.0.

Monolithic unity, I think, has sociological consequences for the propagation of a philosophical system. Holism encourages a certain priestliness in the system's instructors. The sheer bulk and holistic complexity of the system mean that its contributions cannot be transmitted piecemeal. The student must immerse themselves within the system, and learn it like they would a language. The difference between those who understand the system, and those who don't, can't easily be communicated through discrete arguments, and there's an increased tendency to rely upon appeals to the authority of the system's priesthood.

A certain degree of epistemic conservativism is to be expected as a result, among the priesthood of monolithic systems. If every component of the system is strongly reliant of every other component, then revision is costly, and in an effort to ensure only minimal mutilation to the system, there may arise a temptation to disengage from external epistemic challenges.

A modular system doesn't need to be completely acyclic, or arborescent, necessarily, but it should make a virtue of connective sparseness. None of the system's strongly connected components (i.e., regions of the conceptual graph in which each node depends, transitively, on every other -- if the dependency is immediate we call that component a clique) -- I'm setting aside, for now, the question as to whether conceptual dependency is necessarily transitive. On some understandings it might be, but the cloudy and finite nature of human cognition suggests that there may be room for a notion of "intelligibility" that doesn't require chasing things down to their absolute roots. But this is a bigger problem than I'm going to deal with now, in this defragmentation post).

A salient feature of modular systems is that they're relatively easy to teach and learn in piecemeal fashions. And they're relatively easy to revise and refactor. They're also essentially salvageable and reusable by nature -- components of such a system can be put to use in different contexts, even if the system as a whole is held to be unsustainable. These are virtues, of course, that will only seem worth pursuing from a position of philosophical humility. To deliberately construct a system in such a way that it hangs together as a single, holistic monolith, on the other hand, seems like something that could only seem reasonable from a position of arrogance (revision and salvage will never be necessary!) or frivolity (I don't expect my system to be useful to anyone, anyway).

It's been a while, and my memory's a bit foggy, but I remember one of the virtues of Paul Franks' All or Nothing: Systematicity, Transcendental Arguments, and Skepticism in German Idealism being the care with which it took up the relational structure of philosophical systems. I'd like to read it again with graph theoretic properties in mind -- beyond the coarse grained properties of cyclicity (i.e. whether or not the graph has cycles) and arborescence (whether the graph is a tree). It might be fun to go back to the Rhizome/Tree dichotomy of A Thousand Plateaus with these ideas in mind, too.

"Recursivity"

I started reading Yuk Hui's Recursivity and Contingency the other day, and was immediately curious about the title. Why the neologism "recursivity" and not just "recursion"?

He defines the term, and distinguishes it from recursion, a few pages in:

Recursivity is not mere mechanical repetition; it is characterized by the looping movement of returning to itself in order to determine itself,

(and so far, this is just recursion)

while every movement is open to contingency, which in turn determines its singularity.

A word that's commonly used for this second characteristic, in computing, is impurity.

I haven't gotten much further than this, but the guiding thesis of the book seems to be that modern philosophy, at least since Leibniz, has had this idea of "recursivity" -- this synthesis of recursion and contingency -- at the heart of its understanding of nature. The correct conclusion to draw from this, of course, is that modern philosophy should be refactored so that all of the contingency is in main().

Self-Identification

A lot of fuss has been raised, in the debates surrounding "the transgender question", over the matter of legal gender "self-identification", without really making clear exactly what's at stake in this, for us.

It's all very easy to criticize "self-identification" -- especially if you ontologize it, as something that constitutes gender, rather than as something that just tends to reliably report it as experienced and lived-in-the-world -- but have you seriously considered what the alternative amounts to, for us? Or even for cis women like Semenya, for example? The alternative isn't some pat answer about "biology", because we're not debating what constitutes gender, but what regulates it, what stitches it into the fabric of the law. The alternative is coercive identification. It's submitting to identification by others, surrendering your body to their wishes for it, and their fantasies, with no legal leverage to escape it.

And who, after generations of marginalization, violence, and mockery, should we trust to "identify" us, if not ourselves? (Of course, our trust was never requested in the first place.) How will this "identification" take place? How brutal, invasive, or insidious, how tedious and humiliating, will this biopolitical machinery need to be before "cis women, religious women, men, parents, etc." feel "safe" enough to just let us live our lives? And how will this play out for cis women and men? Will they be exempt? How?

The call to recognize self-identification isn't a metaphysical claim at all, I think, when you get to the root of it, though it's been confused for one often enough, and this confusion is responsible for the mistaken impression that "the trans movement" represents -- according to the taste of the critic -- some sort of "essentialism" (because it seems to rest on a notion of gender as something adequately known through eidetic intuition, I guess?), "postmodernism" (because everything that frightens boomers of a certain persuasion is postmodernism, or because it dispenses with "objective reality"), "subjectivism" (because gender, on this account, is just a clear and distinct idea) or whatever.

The call to recognize self-identification is a political question, abstracted away from the opaque and messy biological/psychological/semiotic/social substrate on which "gender", as a political category, supervenes. It's not about what gender is, but about how it should be policed: as little as possible.

What we're dealing with here, in a sense, is what we'd call an "abstraction layer". The ontological makeup of gender, or what we call gender, is no doubt messy as hell. It's a leaky black box, equivocally specified and multiply realized across various heterogeneous materials. I very much doubt that any account of "gender", adequate to the phenomena we expect it to explain, would show it to be just "one thing", or cut nature at the joints. But the precise constitution of that opaque clusterfuck is irrelevant to the abstraction at play. Whatever one's gender is, we're saying that its interface with state power -- to the extent that such a thing is imposed on us -- should be regulated by personal assent.

This isn't, for many of us, the endgame. We may have our sights set on the eventual abolition of gender, as a political category. But for this to come about, I think that we must first refuse, as far as possible, the coercive inscription of that category in our lives.

The Eight Root Statements of the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus as Completed by GPT-2

- The world is everything that is the case.

- What is the case, the fact, is the existence of atomic facts.

- The logical picture of the facts is the thought.

- The thought is the significant proposition.

- Propositions are truth-functions of elementary propositions. (An elementary proposition is a truth-function of itself.)

- The general form of truth-function is: [p,ξ,N(ξ)]. This is the general form of proposition.

- Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.

- Whereof one cannot be silent, it follows that there is a danger of bitter reprivation, of sorrow and grief, of perishing or wandering through the woods. (A loss of quality of a fine bond is both good and bad.)

Epilogue

Okay, clearly most of these fragments could have been perfectly fine standalone posts. But it's refreshing to flush them all at once. P'log does support postdated posting, but, meh... I kind of like the way they all hang together in an incoherent omnibus. Maybe I'll refactor and rework some of them in the future.

I think I'll make a, say, bimonthly ritual of this sort of thing, just to avoid the trap of perfectionism and inertia.